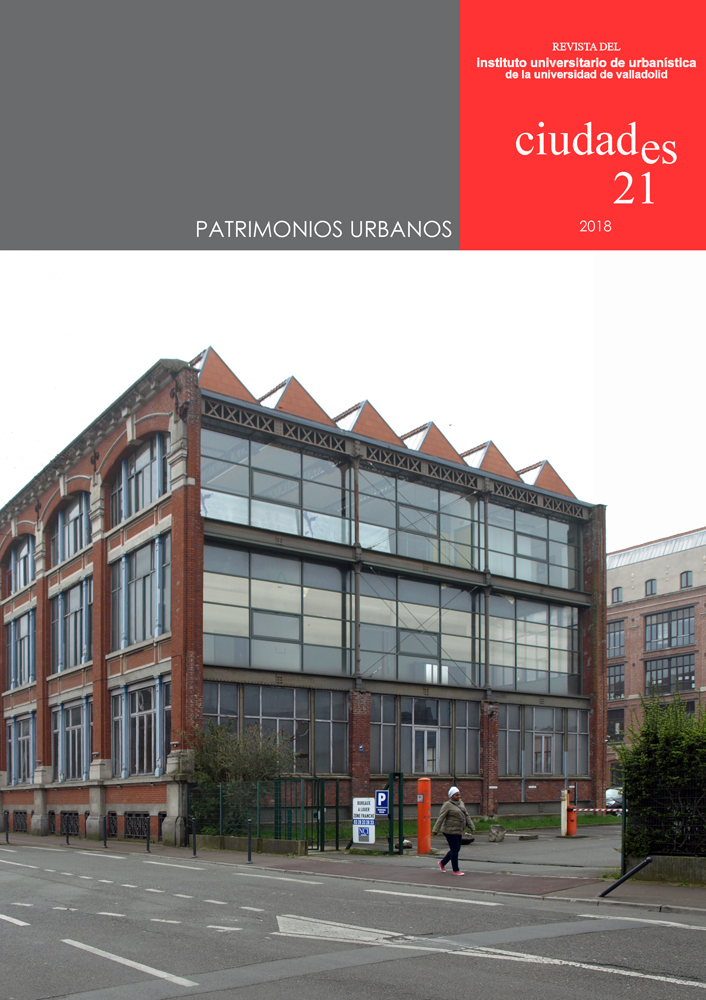

Urban Heritages

Ciudades 21, 2018

MONOGRAPH DOSSIER

Javier PÉREZ GIL

Un marco teórico y metodológico para la arquitectura vernácula

Juan Ignacio PLAZA GUTIÉRREZ

El patrimonio industrial del borde sur de la ciudad de Salamanca

Juan José REYNA MONRREAL

Beyond the Post-Industrial Park: the spatial heritage of Fundidora de Fierro y Acero de Monterrey glimpsed through its workers’ neighborhoods

Beatriz GONZÁLEZ KIRCHNER

Ciudad Pegaso: autarquía y control social. Vivienda obrera asociada a centros industriales

Alberto RODRÍGUEZ-BARCÓN, Estefanía CALO y Raimundo OTERO-ENRÍQUEZ

Reconversión de espacios portuarios y privatización de la fachada litoral de A Coruña: una lectura crítica

MISCELLANEA

Elvira KHAIRULLINA

La planificación urbana y el tráfico rodado: las ideas de Alker Tripp en la URSS

Noel Antonio MANZANO GÓMEZ

Résidencialisation urbaine: seguridad espacial y normalización social en las periferias sensibles francesas

Francisco DINÍS DÍAZ GALLEGO

A Coruña 1967-1974: la construcción vertical de la ciudad

FINAL SECTION

Víctor PÉREZ EGUÍLUZ

Reseña: Attracting visitors to ancient neighbourhoods. Creation and management of the tourist-historic city of Plymouth

Ana RUIZ-VARONA

Reseña: Historias vividas. Grupos de Viviendas en Valencia 1900-1980

Every issue related to heritage has reached, in the last decades, a very relevant presence on the city, while the elements susceptible of being considered from a patrimonial point of view and even the very concepts used have undergone a strong transformation… ostensibly, as nearly each and every ghost that has accompanied these processes of creating heritage in the past are still existing.

There is a point in approaching the heritage question in relation to the city, since from the urban heritage point of view, that, though it hasn’t resolved some outstanding issues, has been consolidated on the regulations as well as the practice, there is a new vision that must now be incorporated, that of the treatment of very diverse heritages that have shaped and shape the city.

To this effect the starting point must be an approximation to the concept of urban heritage, since in the end, it deals with approaching from a diff erent and broader perspective, issues that have been occurring since the very moment of their birth.

Even though it can’t be considered at all as a new matter, to define what is urban heritage remains today a very complex question, difficult to cover within the terms of a definition.

We can take, as a means of approaching this complexity, what Françoise Choay mentioned on the entry patrimoine urbain of the «Dictionnaire de l’urbanisme et de l’aménagement», that she herself directed in 2005 with Pierre Merlin. Urban heritage “comprises the structures, prestigious or otherwise, of cities or urban fabric, preindustrial or from the nineteenth century, and tends to encompass in a general sense every strongly structured urban fabric”. Leaving aside some absences and some controversial aspects of this definition, it’s interesting to note the underpinning idea, that the term urban heritage refers to the urban fabric as a specific type of heritage, or, in other words “the city as heritage”.

This is not and has never been an easy matter. Following the classical argumentative logic, developed by the very same Françoise Choay in her «The Allegory of National Heritage» and summarized in the entry that has been cited, we could consider that the concept of urban heritage was explicitly formulated in the work «Vecchie città ed edilizia nuova», by Gustavo Giovannoni, published in 1931. And what distinguishes Giovannoni’s approach is not that he poses that a city or part of it can have heritage value in and of itself, something that Ruskin had previously noted in «The Stones of Venice», but that it is an heritage that is, and must continue to be, alive. The key issue would reside then in what role this part of the city must perform in contemporary urban life, or, to use Giovannoni’s terms, what are the “acceptable limits of change”.

In his work, Giovanonni proposed several concepts, principles and tools, whose reach and implications could be debatable today –a lot of water has fl owed under the bridge in the last eighty-five years–, but they emphasize, even if it is only budding on occasion, on two main points: the city is a being that must be considered on a global basis, and it is a being that evolves, changes and is transformed.

This two arguments, joined by a third that didn’t appear in Giovannoni’s formulations, that of population and its social and economic circumstances, have configured the basis of an internal debate, heated and more pressing than ever, on how to approach the issue of urban heritage, with landmarks such as the Bolonia Plan, to mention the one best known, that haven’t lost relevance when confronted with practices that little differ from the ideas proposed by Ruskin on the near sacred nature of our ancestors’ legacy, when they aren’t serving a purely marketable view of heritage.

Leaving aside this –basic- questions that would emphasize urban life and its (social, economic) diversity as the main element to preserve, and keeping to the theoretical view, for a good portion of these decades has dominated a perspective geared towards safeguarding certain “historical” urban areas. Unesco’s Recommendation of 1976, known as the Recommendation of Nairobi, was described as “concerning the safeguarding and contemporary role of historic areas”.

Until very recently, then, that which has been sought has been to “save” this urban ensembles and to assign them a current role that, at least in theory, was “compatible with its morphology and scale”, using one of Giovannoni’s expressions.

In fact, many urban ensembles with an officially recognized heritage value (it’s enough to consider those added to the World Heritage List) represent today a prestigious element inside their urban structures… so prestigious that they are the referent to which any other consideration related to the city or its elements is subordinated.

On the other hand, especially from the 1980s onward though it has only hit its stride on the twenty-first century, there has been a sort of transfiguration on the field of heritage, which has translated to the extraordinary expansion of “heritage susceptible” elements followed, simultaneously, by a displacement of the general orientation from the exceptional to the mundane. The conflict between the classical and consolidated urban heritage and these “new heritages” is served, and, paradoxically, in its essence it isn’t that different from the conflict often noted between the monumental heritage and the urban heritage in the past. It’s enough to remember Haussmann and his role in the city of Paris or the practice, already criticized by Camillo Sitte but that hasn’t been yet eradicated, of demolishing the urban environment of certain monuments so they may be better appreciated in all their glory.

Things of the past! That have nothing to do, for instance, with tearing down an industrial building –after all, they are nothing but rubble– to clear the views to a wall, at the same time as they shamelessly build nearby, in front of that very wall, an emblematic and contemporary building, the work of a renowned architect… all in the Holy name of the Heritage.

Curiously, and they aren’t isolated cases, the more the subject of heritage is discussed in some city, the harsher is the battle against some “discordant” elements to a particular vision –and, lest we forget, self-serving– of urban heritage, that understands as such a clearly identified scenography free of elements that may disturb its idyllic perception –sometimes including in this category the population or a part of it–, a sham of a city turned into a show of itself.

Among this elements that are often considered as discordant, and despite the fact that they already have a relevant theoretical journey, it’s relevant to note those linked to the ethnological heritage –and in particular the vernacular architecture– and the industrial heritage, that are often present on many of our cities but that, with a few exceptions, either aren’t considered heritage or, as we have just remarked, are viewed with a myriad of negative connotations.

In the case of vernacular architecture, as its own characteristics and evolution often are ill-suited to mash with the exceptional architectures, even though there’s a clear material connection with the culture and the territory in which they take place.

And, in the case of industrial heritage because many factors converge around its relation with the city. On the one hand, the very evolution of Industrial Archeology (let’s call it that to avoid complex subtleties that would be out of place here), that for a long time has been dedicated rather to safeguarding than knowledge, focusing –deliberately or otherwise– on the edified object, reediting on practice old ghosts of the monumentalist perspective (self-absorption and temporal and Spatial decontextualization), where the preservation of certain elements (more spectacular, “eye-catching” or, simply, better situated”) has been used as a basis for the functional and spatial reconstitution of obsolete industrial spaces.

These spaces, often intentionally named as “empty space” or as “ruins”, have been treated as a reservoir of building land, especially for commercial or residential uses, and on them heritage, if it is at all considered, is subordinated to the project, so the criteria of opportunity tends to prevail over any other.

These two examples, on top of many others that could be considered, lead us to considering the matter of urban heritages, that is, the perspective of heritage from the city’s point of view, instead of the traditional perspective of the city from heritage’s point of view.

In this respect, a new concept has recently irrupted in the urban heritage picture, with the Recommendation on Historic Urban Landscapes passed by Unesco on November, 2011.

Essentially, it applies the concept of landscape as an approach towards urban heritage and therefore, for starters, it would be more adequate to speak of historic urban landscape as a method rather than a concept or notion, even thought the Spanish translation of the Recommendation swapped the term “approximation” for that of “notion”.

It’s undoubtedly an idea full of suggestive implications, but one that given the current state of play hardly results efficient, as the Recommendation doesn’t give a clear definition neither of the notion nor of the method: the same definition, as it’s expressed, is at the very least debatable, and until now has not been developed into an approximation to the two cardinal aspects: the methodology or methodologies that could be used and, even more importantly, the reach that, in practice, this perspective could have, that is, for what could it be useful.

What dominates even today is the confusion, to the point of mixing the category with the tool: cultural landscape, as a specific type of heritage which value resides, oversimplifying matters, in the tapestry of relationships between environment and society (“landscape”), or historic urban landscape, a method based on the notion of landscape that should be used to characterize it in its complexity, even to manage anurban ensemble with heritage values.

Does that mean, then, that the method of historic urban landscape isn’t useful? Not even remotely. Paraphrasing Edgar Morin and his complex thought treatise, it gives the impression that we’re much more advanced and at the same time much more delayed that we may believe. To apply the concepts and methods associated with historic urban landscapes constitutes a formidable weapon, but for it to be useful we must know how to use it and what for.

In terms of our current topic, urban heritages, applying this method should spring from the reformulation of the basis of heritage values on an urban ensemble, that can’t be derived from the existence of a series of monuments, an urban environment or a related group of buildings, whether or not monumental, but from the very same historical process of the city. What creates value that an urban ensemble may have are not the manifestations, more or less exceptional, born from one time period and one set or circumstances, but the fact that they have continued to be integrated in the urban path over the course of the city’s history. And the legibility of this process is precisely what must be preserved.

This isn’t to say that every heritage element must have a similar treatment, but rather that urban heritages constitute themselves as a group that must be understood through its relationships, its agents and its past and present uses.

Therefore, together with –and not in front of– city as heritage, today one must speak as well as the heritage in the city, of the urban heritages without whom we cannot understand neither the city nor urban heritage on its classical sense. All of them, officially sanctioned or otherwise, no matter their time period, their nature, their importance, always relative, and a whole series of attributes that we could considered, on itself and around its relationship system –spatial, temporal, symbolic–, conform a reality of itself, that isn’t equivalent to the mere sum of its parts, and that is lived as an inseparable whole: the city.

Valladolid, May 2018

![]() Avda. Salamanca, 18 47014 · VALLADOLID (España)

Avda. Salamanca, 18 47014 · VALLADOLID (España) ![]() +34 983 184332

+34 983 184332 ![]() iuu@uva.es

iuu@uva.es