Open spaces for public use as a system: complexity and contradiction

Ciudades 26, 2023

MONOGRAPHIC SECTION

Iván RODRÍGUEZ SUÁREZ

Espacios libres indeterminados. El interbloque de los polígonos de vivienda periféricos de Madrid

Ximena ARIZAGA

Espacios de uso público en los conjuntos habitacionales del movimiento moderno: el ambiente urbano en tres casos de Santiago de Chile

Antonio José SALVADOR

El programa Piazze Aperte y la práctica del urbanismo táctico institucional en Milán

Síbel POLAT

Challenges and recommendations in addressing community engagement in public space design in Türkiye

María Paula LLOMPARTE FRENZEL & Marta CASARES

Infraestructura verde y espacios verdes públicos. Reflexiones desde el paisaje en el sistema metropolitano de Tucumán, Argentina

MISCELLANEOUS SECTION

María BARRERO-RESCALVO, Ibán DÍAZ-PARRA, Luz del P. FERNÁNDEZ-VALDERRAMA

Clase, trabajo y gentrificación: la experiencia del doble desplazamiento de los trabajadores productivos en Sevilla

Gonzalo ANDRÉS LÓPEZ, Carme BELLET SANFELIU & Francisco CEBRIÁN ABELLÁN

Buscando límites a la urbanización dispersa: metodología para la delimitación de áreas urbanas en las ciudades medias españolas

Fadrique I. IGLESIAS MENDIZÁBAL & José Luis GARCÍA CUESTA

The potential of the creative economy and the future catalytic effect of Amazon HQ2 in Arlington County

Jesús GARCÍA-ARAQUE & Norma DA SILVA

Aproximación cualitativa a los procesos de integración de los extranjeros en Valladolid y a la incidencia del espacio urbano

Mercedes DÍAZ GARRIDO

Osuna en el siglo XVI. Proceso de formación urbana a través del estudio conjunto del plano y de otras fuentes

FINAL SECTION

Rocío PÉREZ-CAMPAÑA

Reseña: Ordenación del Territorio y Medio Ambiente

Miguel RODRÍGUEZ DE RIVERA HERRERA

Reseña: El arte de leer las calles. Walter Benjamin y la mirada del flâneur

Ricardo SÁNCHEZ LAMPREAVE

Reseña: La Gran Vía de Colón de Granada. Reconstrucción del proyecto y obra de una cala urbana. 1891-1931

The call for papers for this issue proposed open spaces for public use as a topic for debate. The title was perhaps provocative and somewhat ambiguous and was not explicitly explained, although the complexity and contradiction of the open spaces for public use system was already latent in the dilemmas posed. The proposals eventually published have verified these dimensions, providing visions of the heterogeneity of approaches and problems of complex, contradictory open (to) public spaces, but for which it is hoped that a systemic understanding will facilitate not only the analysis of this reality, but also the potential capacity of the whole, greater than that of the parts, to improve our cities and territories.

Before returning to the call for papers and the contributions that have been made to the proposed themes, we bring up Robert Venturi’s famous title for borrowing the two nouns, together, that he used for architecture, although as he rightly points out, many other arts made them their own before. Venturi also insists that his book is concerned only with architectural form. Form is also an innate characteristic of free public spaces, but there are many others for which we find the terms and some of the reflections he develops in this regard very timely: Venturi states that “by embracing contradiction as well as complexity, I aim for vitality as well as validity”, that “a valid order accommodates the circumstantial contradictions of a complex reality”, that “does not ignore or exclude inconsistencies of programme and structure within the order”, that “ambiguity and tension are everywhere in an architecture of complexity and contradiction”, or that “it is perhaps from the everyday landscape, vulgar and disdained, that we can draw the complex and contradictory order that is valid and vital for our architecture considered as an urbanistic whole” (Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, pp. 16, 41, 20 and 104, 1977, 2nd edition [1966]).

In the call we said that one of the many disturbing scenes left by the pandemic has been that of parks that were first closed and then marked out by circles in which to locate and distance the different groups living together; and in the opposite sense, that this compressed time has also accelerated and amplified the environmental valuation of these spaces. The compatibility, or not, of the two visions can synthesise what we were looking for in this issue: can we speak of a system of open spaces that enhances health? To what extent and with what keys can such a system be a trigger or motor of urban regeneration, or, on the contrary, adapt to the status quo, with greenwashing as a reinforcer of processes of gentrification and socio-spatial inequality?

With reference to the first question, it is not surprising that the issue of urban health, as the main theme of the previous issue (Ciudades 25. Paths toward a healthier city), has already given rise to articles in this direction, focusing directly on public open spaces, or making a large part of the proposed “solutions” fall on it. These two fully do it: “Prevención en salud desde el diseño del espacio público. El proyecto URB_HealthS como experiencia de transferencia de conocimiento” (by María Cristina García-González, Ester Higueras García, Cristina Gallego Gamazo, Elisa Pozo Menéndez & Emilia Román López); and “Valoración de la proximidad a las Zonas Verdes Urbanas de la ciudad de Zaragoza como estrategia de adaptación a situaciones pandémicas” (by Natalia Bolea Tolón, Raúl Postigo Vidal & Carlos López Escolano); but practically all the articles in the issue included in their discourses the healing, preventive or curative capacity of public spaces (from active urbanism, to proximity urbanism, to school paths, etc.). We encourage you to review them.

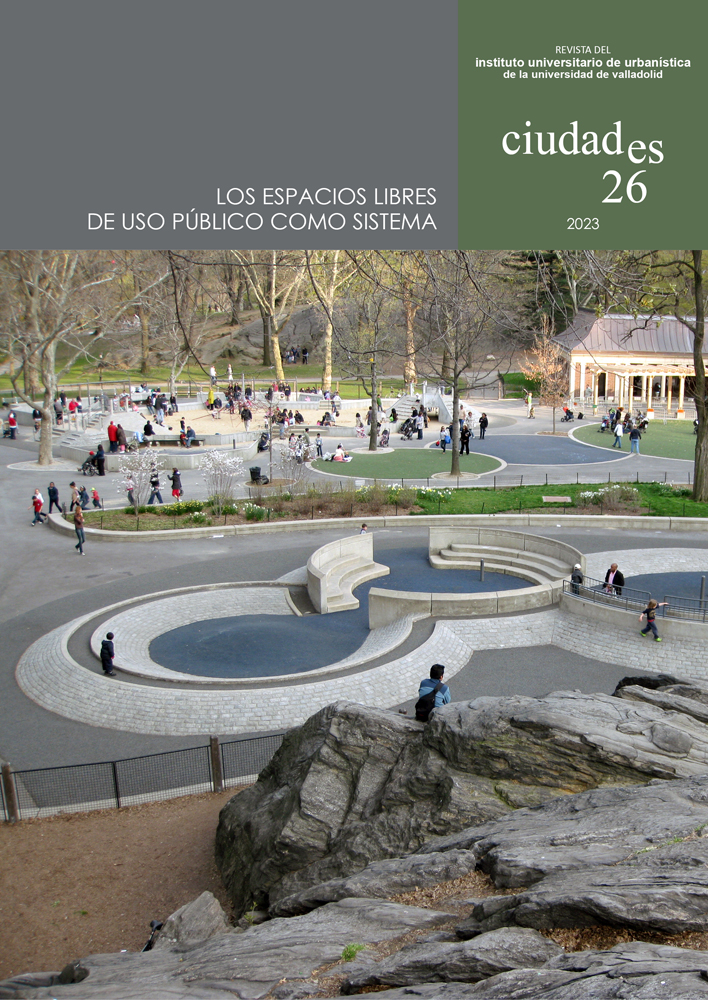

Regarding the second question, we can see public spaces as a symptom or trigger of many other realities characteristic of the contemporary urban, global and local. In these times of socio-environmental crisis, on the one hand, it seems that many expectations are placed, and confidence is placed in the salvific capacity of public open spaces per se, although on the other hand, for some time now, the death of public space, of all public spaces in general, has been foreshadowed (citing another reference, M. Sorkin, ed. Variations on a Theme Park. The New American City and the End of Public Space, 1992). The different denominations of the object in question (open, collective spaces, co-places…) and even more if we incorporate the issue of form or greenery (squares, parks, green areas…), each one insists on one or other orientation and sometimes evade the commitment to others. It is impossible to pay equal attention to so many themes in the same discourse, but, as we shall see, it can be very interesting to make transversal readings between some of the proposals presented, changing angles of vision. We warned at the launch of Sennet’s reflection on the construction of Central Park as a bitter alternative, of relief, to the complexity of urban life experienced in the street (in The Consciousness of the Eye, 1990). In any case, both, street and park, are for the moment mostly associated with public space as a common good (Lefebvre).

We also mentioned in the call for papers two publications from about a decade ago, edited by the Instituto Universitario de Urbanística of the Universidad de Valladolid: Espacio público en la ciudad contemporánea. Perspectivas críticas sobre su gestión, su patrimonialización y su proyecto (Mireia Viladevall i Guasch & María Castrillo Romón, coords., 2010); and issue 1 of the series Dossier Ciudades, “Corredores Ecológicos” (Luis Santos y Ganges & Pedro María Herrera Calvo, coords., 2012), compilations of diverse voices that can be a good excuse to reflect on the trajectories and realities of the open spaces for public use in these ten years and on its future, with very diverse risks, challenges and opportunities. Moreover, boths publications place us at the two extremes of reflection on an extended system of open spaces which, under the umbrella of the so-called green infrastructure, can cover the entire connected territory, although the keys to analysis, service and use will necessarily be different if we want to interpret its urban, metropolitan or even rural essence. Finally, we wondered whether, after the very corporeal experience of re-encountering post-confinement open spaces, this might be a unique opportunity to consolidate ecofeminist theories on caring for each other and for our common habitat. In the end, it has not been possible to publish any proposals in this regard, although we expect them in future issues.

The resulting selection for the monographic section is not extensive, five articles, but we consider that they all underlie the complex, contradictory and systemic dimensions that the call for papers demanded. The authors have detected, from different perspectives, contradictions, complexities and many values in the observation, planning, project, management and, above all, capacity to be used, practised and inhabited in different types of open spaces. These are articles rich in nuances, from five different geographical origins, all five looking at processes that start from several moments in time, but all from the present, in and between which problems and learning for the future are interwoven. In particular, the first and second on similar open-block fabric, and the third and fourth on diverse participatory processes, could respectively establish very interesting dialogues. The type of urban fabric of the third case study also coincides with the first and second, although the focus of attention in that does not arise from the morpho-typology, and the three cases, in turn, are at different moments of urban degradation-regeneration processes. We advance some approaches in a particularised way:

In the first article, by Iván Rodríguez Suárez, of the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, morphological and, above all, legal indeterminacy seems to be the cause, curiously, of the lack of clear functionality of the inter-block open spaces of some functionalist housing estates in the first periphery of Madrid. Legal uncertainties over the ownership of unoccupied land have served as an excuse to freeze their possibilities for improvement and maintenance. The author meticulously research to reconstruct the legal process undergone by these estates from their origin to the present day and how planning has tried to deal with this indeterminacy both in terms of internal improvement and their integration into the city. In spite of the legal handicap, he does not finally renounce to express the opportunity of working with these spaces “in the current context of health, energy and climate emergency”, moving from the complexities and contradictions intrinsic to the processes to the necessary systemic vision: “General planning and the integrated management of public land assets, trying to redistribute rents on an urban scale, could contribute to solve the problems and take advantage of the opportunities of these fabrics”.

In the second article, Ximena Arizaga, from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, carefully reconstructs the ambiance (according to Augoyard, “emerging characteristic of the relationship between physical and sensitive space, uses and inhabitant practices”) of three modernist housing complexes, also with towers and blocks, in Santiago de Chile. And it does so, first from the planimetric analysis and then from the recurrent observation of their open spaces, in order to identify use and outstanding environments, uses between the (legal) destination that is permitted and the practices, which are given, uses charged with meaning, which give meaning to the space. Thus, what in the first article is a priori a problem, here, in a certain way, is valued, expressed as “delivery of a generous collective space, open and permeable to the rest of the neighbouring city”, as opposed to the current complexes of equipped towers “for exclusive and privative use”. Property is obviated (although we could ask ourselves about it) in order to focus on the morphological characteristics that favour one type of practice or another and that in synthesis determine the “environments”. The author concludes that there is coherence (understood as the absence of contradiction) when the space is adapted to the uses it accommodates, and these uses, together with spatial and sensitive characteristics, favour active practices of public space. Precisely, from the classification he makes into squares, connectors, “backwaters”, and fragments, she highlights the preference for spaces that are less in line with the archetypal ones, as opposed to the square as “esplanade”, the backwaters on the trail, a pause on the path, and the connectors, with the dream of the three-dimensional city in the elevated ones, which, despite their problems, offer multiple opportunities. This is a piece of research focused on the spatial and social qualities of spaces of mediation between private intervention and public space and their possible new life that will allow us to move towards a better understanding of the keys to “good density”.

The third article focuses on the participatory process for the (re-)design of Piazza Gasparri, in the Comasina neighbourhood, built in the 1950s in the Milanese periphery according to CIAM postulates. Antonio José Salvador, from Politecnico di Milano, reconstructs and evaluates this process as part of the Piazza Aperte programme, one of the priority strategies within the territorial governance plan, which aims to “transform low-quality local spaces postulated by citizen collectives”. The programme resorts to the so-called Tactical Urbanism as an experimental tool for a first provisional transformation of public space, mostly by volunteers and at low cost, placing the promoters that emerge from civil society not as mere users, but as protagonists of the process; evaluating in a following phase its possible passage to permanent. The author, after analysing the various questionings of the institutionalisation of a practice that emerged as subversive and alternative, describes in detail the process followed in the case study, including the perspectives of its neighbourhood protagonists, aware that they do not represent the multiculturalism of the neighbourhood and with uncertainties about their generational replacement. The final reflections go back over a complex and multidimensional type of process that the administration can undervalue and end up transforming into just another plan, but which can also give excessive responsibility to intermediary protagonist groups and exacerbate “asymmetrical practices”.

The fourth article also deals with the topic of participation, but a priori in the midst of processes far removed from the Milanese one. Síbel Polat, professor at Bursa Uludağ Üniversitesi (Türkiye), evaluates in parallel three very different cases of redesign of public open spaces in three Turkish cities. Despite the disparity of scales, places and processes, all three cases show some significant element of participation in the advancement of citizen involvement in Turkish society. The three cases are analysed systematically according to four dimensions or stages of the process: the legal and institutional context, the instruments available for participation, the coordination between actors, and the implementation of urban design. In the different stages, numerous themes appear around participatory procedures and their contradictions, which can be transferred to almost any scale and culture: whether a culture of participation implies education in participation, the unknowns that digital tools provoke in the transparency of the processes, the differences between informing, involving or having decision-making capacity, the timescales of participation versus those of political agendas, etc. As the author says, the work aims “to find new ways to strengthen community engagement in public space design” that contribute to a higher quality in public spaces for sustainable cities. Surely the questions that arose from the previous research on the Milanese case, apparently at a more evolved stage of participatory processes, can also contribute to this.

Finally, the fifth article of the monograph, by María Paula Llomparte Frenzel and Marta Casares, from the Universidad Nacional de Tucumán (Argentina), expands the focus to address the contradictions that the potential green infrastructure of the metropolitan system of Tucumán brings back to us, particularly in what they call the urban-rural interface territory. The authors argue that conceptualisations of the urban from the landscape, together with instruments such as the green infrastructure, can change the way of approaching relations between territories; on the contrary, the lack of an integrating vision, with adequate inter-jurisdictional governance mechanisms, leads to a worsening of social and environmental vulnerability. This is the case in rural-urban interface strips of the metropolitan system of Tucumán, where, despite the presence of elements of great value such as green infrastructure, paradoxes multiply. In some cases, it is the market that appropriates the discourse of a “more harmonious relationship with nature” for real estate development on fragile soils, which at the same time prevents access to a large part of the highland population. In other cases, environmental values are left unprotected by informal occupation, while the social vulnerability of these occupations is exacerbated by the lack of nearby green spaces. The concepts and instruments of the green infrastructure have at least helped the authors to highlight the socio-environmental imbalances, hoping that they will also contribute to redressing them and establishing more harmonious links among society, nature and built environment.

As we said at the beginning, the cross readings can be multiple: tactics, strategy, form, property, proximity and systemic view, urban densification and rural dispersion, negative and positive imaginaries associated with one or another type of urban fabric and its associated open spaces, in the “plaza”, in a green-park infrastructure capable of being appropriated, in the inter-block backwater, regulating or not regulating wills… In short, the five articles debate between the selective appropriation and the commitment to the commons of each of the agencies, individual and collective, that intervene in the definition of open spaces for public use, from design and management to practices. This diverse panorama presents processes that are recognisable almost everywhere and therefore from which experiences can be learnt and exchanged, but which are expressed from a specific legal, social, political, and environmental context, which needs to be understood. Recalling the different geographical origins of each of the proposals (in order: Spain, Chile, Italy, Türkiye and Argentina), we can ask ourselves how far or how close we feel to these realities and identify with their techniques and practices.

On this occasion, the miscellaneous section has been very fruitful, and we have five other articles on various urban and urbanistic themes of great interest. María Barrero-Rescalvo, Iván Díaz-Parra and Luz del P. Fernández-Valderrama, from the Universidad de Sevilla, confront us with the double process of displacement suffered by the artisan working classes from the centre of Seville in a context of gentrification and tourist development; first, residential expulsion, and then of artisan work, processes that feed off each other, leading in turn to the disappearance of productive spaces in the centre and the promotion of a speculative and unproductive economy. We could glimpse a certain relationship or tension between the phenomena verified in this research and those that could be provoked regarding the potential expectations for the “creative classes” of the announced installation in Arlington County (Virginia) of a new Amazon headquarters, subject of the article by Fadrique I. Iglesias Mendizábal and José Luis García Cuesta, from the Universidad de Valladolid. Gonzalo Andrés-López, Carme Bellet Sanfeliu and Francisco Cebrián-Abellán, from the Universities of Burgos, Lleida and Castilla-La Mancha respectively, present an ambitious proposal for the delimitation of urban areas of medium-sized Spanish cities with the determination of the Urban Transformation Index of these areas, based on cartographic analysis together with multiple statistical data, applying their methodology to 34 inland cities in the period 2000-2020. They hope that the indicators resulting from this method will facilitate the design of more effective inter-municipal strategies in terms of sustainability. Jesús García-Araque and Norma Da-Silva, from the University and Courts of Valladolid, analyse the integration of the foreign population in this city and its spatial translation by neighbourhoods, through a qualitative approach, with interviews with foreigners and staff from related associations, observing how the concern for employment conditions the perception of integration. Finally, Mercedes Díaz Garrido, from the Universidad de Sevilla, reconstructs the map of the city of Osuna in the 16th century on the basis of documentary and archaeological sources and the study and drawing of the urban form itself as a method both of synthetic knowledge of what exists and of future incorporations in a constant learning process of the city as a historical construction.

Finally, this issue is completed by three reviews of three recent books with different characteristics and authorship. In the first, Ordenación del Territorio y Medio Ambiente (2022), 41 authors reflect on a transversal discipline, technique and policy and its future. In the second, El arte de leer las calles. Walter Benjamin y la mirada del flâneur (2021), its author, Fiona Songel, studies the evolution of the city in the 19th and 20th centuries, with the flâneur as the object of analysis, through the texts of Walter Benjamin; it is that flâneur, the fruit of the modern city, who in his urban wandering “botanises the asphalt”. In the third and last book reviewed, La Gran Vía de Colón de Granada. Reconstrucción del proyecto y obra de una cala urbana. 1891-1931 (2021), its author, Roser Martínez Ramos e Iruela, manages to transfer in an original way the results of her doctoral thesis on the design and construction process followed for the materialisation of the modern Gran Vía of Granada.

Faced with the environmental and social challenges of the historical times in which we find ourselves, the journal Ciudades continues to be committed to building a knowledge of the urban that facilitates confronting them. On this occasion, we have focused on the complexities and contradictions of public open spaces as a system, where the living or dying spirit of (urban) life rests. If we trust in the permanence of this life, public open spaces will continue to be an inexhaustible subject of research, although, surprisingly, there are not as many recent articles in academic journals on the subject as one might expect. From the contributions presented here the journal concludes that in order to move towards a vital public (and free) open space, multiple commitments are needed, from governance, from technical bodies and administrations, from citizens, from those who use the spaces, and from projects, plans and strategies that do not homogenise subjects or territories.

Valladolid, may 2023.

![]() Avda. Salamanca, 18 47014 · VALLADOLID (España)

Avda. Salamanca, 18 47014 · VALLADOLID (España) ![]() +34 983 184332

+34 983 184332 ![]() iuu@uva.es

iuu@uva.es