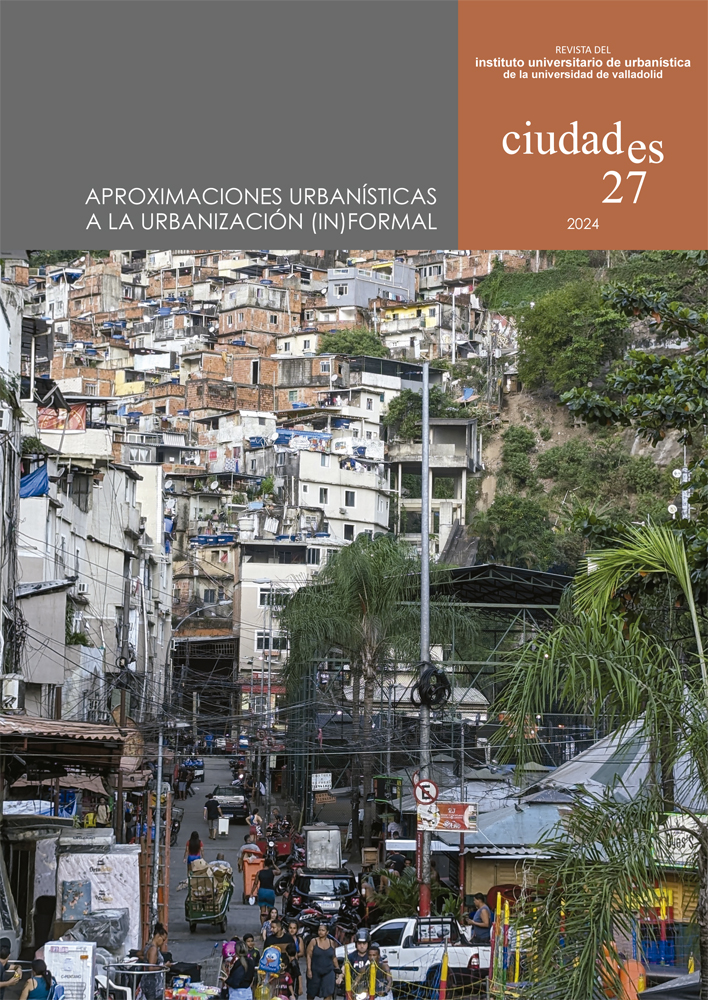

Urbanistic approaches to (in)formal urbanisation

Ciudades 27, 2024

MONOGRAPHIC SECTION

Patricia FRAILE-GARRIDO & Inés MARTÍN-ROBLES

From Barn Raising to Community Empowerment: the legacy of Karl Linn and John Turner

Andrés GODOY OSSANDÓN

El estudio de la informalidad urbana y habitacional en América Latina y Chile: principales perspectivas y debates

Florencia BRIZUELA

De las “villas miseria” a los “asentamientos informales”. Problematizaciones estatales sobre la cuestión habitacional en Argentina (1955-1990)

Luiza Farnese Lana SARAYED-DIN & Luiz Alex Silva SARAIVA

Urbanism(s) and informality(ies) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Solange ARAUJO DE CARVALHO

Discutindo a urbanização de favelas: analise de práticas formais e da “lógica da favela” no Morro do Alemão, Rio de Janeiro

Stella SCHROEDER

La producción informal de espacios públicos en asentamientos humanos de Piura (Perú)

Manlio MICHIELETTO & Victor Bay MUKANYA KAYEMBE

Analysis of a planned neighbourhood of Kinshasa and its mix with spontaneous extension neighbourhoods: the case of the Maman Mobutu City

Jesús LÓPEZ DÍAZ & María Adoración MARTÍNEZ ARANDA

El chabolismo madrileño bajo el franquismo: urbanismo y control social desde 1939 hasta el Plan de Absorción del Chabolismo de 1961

Luciane MENDES, Esteban DE MANUEL JEREZ & Marta DONADEI

Caracterización y evolución de los barrios de autoconstrucción de Sevilla (España)

Cristina BOTANA IGLESIAS

Más allá del desalojo: análisis sobre actuaciones según lógicas de arraigo en asentamientos precarios de población gitana en Galicia

Javier PÉREZ GIL

Asentamientos informales y arquitectura vernácula: viejos y nuevos debates

MISCELLANEOUS SECTION

Helena PUERES ROLDÃO, Eduardo Augusto WERNECK RIBEIRO & Mario Francisco LEAL DE QUADRO

A importância de um instrumento local no combate às ilhas de calor: diretrizes para reorientar o uso do solo

FINAL SECTION

Rodrigo ALMONACID CANSECO

Reseña: La cultura arquitectónica en los años de la Transición

Rubén PALLOL TRIGUEROS

Reseña: European Planning History in the 20th Century. A Continent of Urban Planning

The term “informal” appeared in 1971 in the work of the English anthropologist K. Hart. Hart and, shortly after, in 1972, in the so-called “Kenya Report” of the International Labor Office, which characterized the “informal activities” that gave shape to an “informal economy”. Later, the notion of informality, born in the field of Economics, was introduced in urban studies and, in particular, in Anthropology and Geography, which studied the so-called cities of the South and faced the problem of describing their development. The use of the notion of informality thus slipped from the field of economic activities (where the tangible dimension of the processes may be of little significance) to that of housing and urban planning, where physical space occupies a central place.

More recently, the conceptualization of informality forged mainly in the global South circulated to the North, where it has been used in the analysis of current processes and also in the study of historical issues. This has culminated in a series of conceptual transpositions between disciplines and between historical contexts that raises a number of questions about the knowledge and descriptive models produced. In fact, “informal urbanization” today amalgamates objects and processes that have previously received other names, very different according to countries, moments and agents.

On the other hand, although urban research on this object has a long trajectory and has been developed from various critical perspectives in many countries of the so-called global South, in Europe, interest in the phenomenon has been more discontinuous. In Spain, the problem of shantytowns and the consolidation of a new generation of intervention policies in slums were accompanied, between 1970 and 1990 approximately, by a boom in scientific production on the phenomenon of slums from different perspectives, both geographical and sociological and urbanistic-projectual, including the translation of landmark works such as those of John F. C. Turner. Later, since the 2010s, in a transnational manner, a certain resurgence of the issues of informality has been appreciated, both in the so-called informal turn in urban sociology in recent decades and, for example, in the field of historical research, with the momentum acquired by the History of Informal Urbanization.

The present issue of the journal Ciudades contributes to this panorama with the objective of deconstructing the notion of informality, a notion that, in general terms, has been used to designate the unplanned or not subject to the normativity of public institutions, and that, as a consequence of the above, has ended up constituting a homogenizing and universalist conception of the “unplanned”.

In fact, as a whole, the articles in this monograph “Urbanistic Approaches to (in)formal urbanization” show the heterogeneity of situations, casuistry and processes that, beyond their socio-spatial specificities, tend to be covered and homogenized by the questioned notion. The recognition of this diversity – that is, of informalities, in plural – and of (in)formalities in their transitoriness and hybridizations is fundamental to overcome the rigid and static planned/unplanned (or formal/informal) dominant binomial, and to construct new categories that express the diversity of socio-historical, political and cultural conditions as essential parameters of the development of cities and that free urban analysis from reductionist schemes of thought.

In particular, the article by Luiza Farnese Lana Sarayed-Din and Luiz Alex Silva Saraiva, “Urbanism(s) and informality(ies) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil”, addresses the theoretical-empirical discussion of certain urbanistic issues that challenge the formal/informal dichotomy and the “dominant developmentalist narratives”, and intertwines and confronts them with the analysis of Brazilian popular culture and urbanism in Rocinha and Porto Maravilha (Rio de Janeiro). It underlines the dominant and contradictory character of a perspective that defines urbanism, urban landscapes and development through the prisms of universalism, hierarchy, control and statistics, and points to the need to construct a broader theoretical discourse that embraces cities, contexts and urbanisms such as those of the global South. Within these emerging theoretical constructions, they identify important contributions made from the global South to the conceptualization of informality, contributions that, in addition to re-evaluating the epistemology of urban planning, confront the dominant current in urbanistic thought and struggle to make diverse urbanisms visible -as do, on another level, the inhabitants of the favelas studied-.

For her part, Florencia Brizuela “De las ‘villas miseria’ a los ‘asentamientos informales’. State problematizations of the housing issue in Argentina (1955-1990)” carries out an interesting exercise in deconstructing the lexicon of informality. Adopting a critical history of thought approach, this work shows not only that the way of naming a problem connotes the perspective of the namer (in this case, the Emergency Plan of 1956 and the Arraigo Program of 1991) but also that it is pregnant with an important symbolic charge in terms of the orientation of public action (the dictatorship of the Liberating Revolution and the government of Carlos Menem, respectively). He also contributes that, for decades, a veridiction has been built in Argentina (Foucault) that is expressed in the insistence that the State should abandon its competencies in informal urbanization and shift them to families and the private sector.

Andrés Godoy Ossandón, in “The study of urban and housing informality in Latin America and Chile: main perspectives and debates”, shows the richness and dynamism of Latin American scientific production on urban and housing informality, which he organizes on the basis of Tomer Dekel’s proposal to structure in five perspectives that have sought to explain the existence and persistence of informal housing and neighborhoods throughout the world, and moves towards a diachronic perspective of the specific currents of thought that structure the scientific debate in Latin America in general, and in Chile in particular. In this journey, Godoy recognizes the moments of emergence and periods of greater incidence of each current, the influence of the diverse historical contexts, the contributions that achieved greater relevance and the criticisms that had more weight in the advance of reflection.

In another framework of theoretical questioning, the article “Informal settlements and vernacular architecture: old and new debates”, by Javier Pérez Gil, shrewdly enters into two recent and very lively debates on informal settlements, one linked to their relationship with vernacular architecture and the other, associated with the previous one, which questions the possibility of categorizing them as cultural heritage. Their analyses point out that both debates do not depend so much on the epistemological consideration of informal settlements themselves as on the prior conceptualization of vernacular architecture in itself and as heritage.

From a more empirical perspective, the article “Caracterización y evolución de los barrios de autoconstrucción de Sevilla (España)”, by Luciane Mendes, Esteban de Manuel Jerez and Marta Donadei, focuses on the analysis of the origin and development of the so-called “barrios de autoconstrucción” of Seville, and their characterization and typification by virtue of their spatial, social and cultural and juridical-administrative dynamics. The authors note that, although born with a “strong vulnerability”, many of these neighborhoods have managed to achieve “full integration”, becoming dynamic and complex neighborhoods. In doing so, in addition to recognizing these neighborhoods as a model of social production and management of habitat, they verify that the practice of self-construction and “progressive architecture” have been able to constitute an adequate and appropriate solution to facilitate access to housing for the population with few economic means.

Three contributions discuss issues associated with public urban planning intervention in neighborhoods of informal origin. This is the case of the work by Jesús López Díaz and Mª Adoración Martínez Aranda, “El chabolismo madrileño bajo el franquismo: Urbanism and social control from 1939 to the 1961 Shantytown Absorption Plan”, which proposes a historical analysis describing the state policies adopted in Spain in the 1940s and 1950s, under Franco’s dictatorship, in response to the overwhelming and very serious problem of precarious housing, taking as a case study the capital, Madrid, and placing special emphasis on the 1957 Social Emergency Plan.

Jana Donat (“El Plan Nacional de Relocalizaciones en Uruguay: ¿combatir el crecimiento urbano informal o revivir sus causas?”), focusing on the two modalities of the relocation program of the “asentamiento” of La Chacarita (Montevideo), shows the colliding temporalities of the public agents involved (especially the Municipality of Montevideo) and of the residents who were forcibly relocated. It also shows how the formalization of housing and socio-spatial practices affects the relationship between residents, the State and the market.

In “Beyond eviction: analysis of actions according to the logic of rootedness in precarious settlements of the gypsy population in Galicia”, Cristina Botana Iglesias analyzes and diagnoses, based on the case studies of three “precarious settlements” characterized by antigypsy territorial exclusion, other types of specific practices: housing replacement, targeted rehabilitation and assisted self-construction. All of them are based on “rooting logics” and are proposed as alternatives to dismantling or eviction-eviction practices, but they differ in their different levels of institutional control over the processes. From the study of these experiences, including the strategies of self-management and resistance developed, four keys emerge that could be incorporated into the design processes of public policies for urban improvement, which implies an implicit understanding of slums as places that produce urban knowledge and contribute to overcoming the analyses that describe them as urban anomalies or subordinate spaces without their own agency.

Two texts focus their analysis on various forms of effective interaction between planned and unplanned urban practices. Solange Araujo de Carvalho, in “Discutindo a urbanização de favelas: analise de práticas formais e da lógica da favela no Morro do Alemão, Rio de Janeiro”, refers to the Programa de Aceleração do Crescimento (PAC, which also partially surfaces in the article by Sarayed-Din and Saraiva) and, based on the case of a well-known favela carioca, reviews how the complex system of dynamics, practices and actors that he calls the “logic of the favela” has interacted at the architectural and urban scale with some important gaps in public action in the “favela urbanization” operations of that program. For their part, Manlio Michieletto and Victor Bay Mukanya Kayembe, in “Analysis of a planned neighborhood of Kinshasa and its mix with spontaneous extension neighborhoods: case of the Maman Mobutu City”, examine various factors that have determined the decline in the urban evolution of this African “Garden City” built in the 1980s, among them, some informal processes of spatial transformation and also the socioeconomic inequalities with the so-called “spontaneous neighborhoods” of its surroundings.

The role of the inhabitants in the urbanization processes is the focus of two very different contributions. Stella Schroeder (“La producción informal de espacios públicos en asentamientos humanos de Piura, Perú”) focuses her analysis on the free spaces for community use (“espacios públicos”) for sports, recreational and meeting uses produced by the inhabitants of certain “human settlements” of informal origin in a medium-sized Peruvian city. Patricia Fraile-Garrido and Inés Martín-Robles, in “From Barn Raising to Community Empowerment: the legacy of Karl Linn and John Turner”, approach the intellectual legacy of these two personalities, respectively, of American landscape architecture and architecture. Although no link between them is recorded, their ideas and trajectories present affinities that the article highlights, among others, the importance they give to community participation in the construction of the spaces they inhabit and its value as a tool for the development of the communities themselves.

Finally, this issue of Cities closes with an article from the miscellaneous section signed by Helena Pueres Roldão, Eduardo Augusto Werneck Ribeiro and Mario Francisco Leal de Quadro, and dedicated to “The importance of a local instrument in the fight against heat islands: Guidelines for redirecting land use”; and with two reviews: one by Rodrigo Almonacid on the book La cultura arquitectónica en los años de la Transición, coordinated by Carlos Sambricio and published in 2022 by Editorial Universidad de Sevilla; another by Rubén Pallol of European Planning History in the 20th Century. A Continent of Urban Planning, coordinated by Max Welch Guerra et al. and published by Routledge in 2023.

Valladolid, May 2024

![]() Avda. Salamanca, 18 47014 · VALLADOLID (España)

Avda. Salamanca, 18 47014 · VALLADOLID (España) ![]() +34 983 184332

+34 983 184332 ![]() iuu@uva.es

iuu@uva.es